Article by Wayne Gillam, photos by Ryan Hoover / UW ECE News

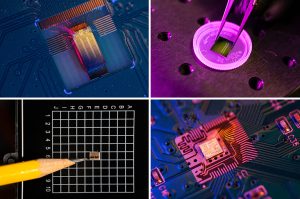

Clockwise, from upper left: Microchips designed by UW ECE faculty members Sajjad Moazeni, Mo Li, Chris Rudell, and Hossein Naghavi

Microchips can be found in almost every device that uses electronics, from smartphones and microwave ovens to satellites and supersonic jets. These tiny chips are so commonplace we take them for granted, but they are a wonder of modern engineering.

A microchip, also called a semiconductor chip or an integrated circuit, is a layered set of electronic circuits built onto a small, flat piece of silicon. These chips are manufactured on a microscopic scale, and the components that make up this intricate latticework (such as transistors, resistors, and their interconnections) are so tiny that their dimensions are measured in nanometers. That is incredibly small. To put it into perspective, a sheet of paper is about 100,000 nanometers thick. Some microchip components are now under 10 nanometers wide, which makes it possible to fit billions of transistors onto a single chip.

Microchips can be further defined by the type of integrated circuitry they contain and by their function. In terms of circuitry, a chip can be digital, analog, or mixed signal. In digital circuits, signals are binary (either “on” or “off”). In analog chips, the signals are continuous, meaning they can take on any value in a given range. And mixed-signal chips are what they sound like, chips that handle both digital and analog signals. In regard to function, there are four main categories: logic chips, which are the “brains” of electronics that process information to complete a task, memory chips for storing information, application-specific integrated chips, or ASICs, which are customized for a particular use, and system-on-a-chip devices, or SoCs, integrated circuits that combine electronic device components onto a single chip. SoCs incorporate a large, complex electronic system, which about 50 years ago would have required an entire building to house.

“The UW is already the biggest hub in chip design in the Pacific Northwest. I want to contribute to improving that standing and making sure students in this area can get a comparable or better education than anywhere else in the nation.” — UW ECE Assistant Professor Ang Li

UW ECE faculty design all these different types of microchips and are leaders in the field today. These faculty members are known for creative, interdisciplinary approaches to chip design and development, and they have strong collaborations with industry. They also have access to the Washington Nanofabrication Facility for building chips on-campus as well as support from the Department, which has designed academic pathways for undergraduate students interested in pursuing a career in the semiconductor industry. Together, these elements combine to put UW ECE at the forefront of microchip design, enabling the Department to offer unique educational opportunities for students.

In addition, federal and state support for the semiconductor industry, such as that from the CHIPS and Science Act, will continue to feed manufacturing and workforce development for the foreseeable future. UW ECE is well-positioned to leverage this funding and support, which stands to provide more opportunities for students and faculty, strengthen existing collaborations in the field, and create new industry, government, and community partnerships.

Learn more in this article about several UW ECE faculty members who specialize in microchip design, the focus of their research, and the opportunities they provide students.

Ang Li

UW ECE Assistant Professor Ang Li

UW ECE Assistant Professor Ang Li designs advanced digital microchips that are tailored to, but not limited by, specific application needs. He directs the PN Computer Engineering Lab at the UW, which focuses on innovating a variety of devices ranging from computing systems to integrated circuits. The lab also explores the interplay between classic and emerging computing technologies. Li specializes in chips that he calls “domain optimized,” meaning that chips designed in this way are optimized for specific applications, but they can be used for other purposes as well. Some of the application areas Li designs chips for include artificial intelligence and machine learning, high-performance computing for scientific studies and simulations, data centers that support cloud computing, and emerging technologies like quantum computing.

Li is relatively new to UW ECE. After graduating from Princeton University in 2023 with a doctoral degree in electrical and computer engineering, he spent a year as a visiting postdoctoral scholar with Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) and joined UW ECE as an affiliate assistant professor. In September 2024, he joined UW ECE full-time as a tenure-track assistant professor. Li’s lab has been focusing on chip modeling and simulation, and he anticipates forming strong industry collaborations with companies such as AMD, Intel, Apple, Nvidia, and Qualcomm. He currently has opportunities for students to work on state-of-the-art research projects in his lab. He also noted that he can pair undergraduate and graduate students with his doctoral students to help provide a better understanding of how research is conducted.

“The UW is already the biggest hub in chip design in the Pacific Northwest,” Li said. “I want to contribute to improving that standing and making sure students in this area can get a comparable or even better education than anywhere else in the nation.”

Sajjad Moazeni

UW ECE Assistant Professor Sajjad Moazeni

UW ECE Assistant Professor Sajjad Moazeni directs the Emerging Technologies and Integrated Systems lab at the UW, which develops digital, analog, and mixed-signal microchips that have applications in computing and communications, sensing and imaging, and the life sciences. Moazeni’s work blends state-of-the-art electronics with photonics and other emerging technologies. His lab focuses on all critical aspects of emerging integrated technologies, from fabrication and integration methods to system-level and architectural analysis in order to build next-generation, integrated systems. Specific applications for Moazeni’s chips include light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems for self-driving vehicles, optical interconnects for data centers that support artificial intelligence and machine learning in the cloud, and endoscopes for medical imaging and interventions. He also develops cryogenic optics for quantum computing, which he collaborates on with UW ECE and Physics Professor Mo Li.

Moazeni’s strong industry partnerships, cutting-edge research, and openness to new ideas and approaches provide students with opportunities to learn about leading-edge technologies that they might not find elsewhere. His industry and institutional collaborators include GlobalFoundries, which helps support silicon photonic chip fabrication, and Fermilab, the nation’s particle physics and accelerator laboratory. Recently, Moazeni has been bringing AI and machine learning into some of the lower-level tasks involved in chip design, such as generating simulations, and he has been automating some parts of his design flow using generative AI.

“The area of photonics and optical devices that need to be fabricated and packaged with electronics is something very new. It’s not a part of any typical course curriculum, and it is very rare, even in graduate-level courses,” Moazeni said. “I embed this topic into some of the courses that I teach, and my lab offers many unique research opportunities for graduate and undergraduate students.”

Hossein Naghavi

UW ECE Assistant Professor Hossein Naghavi

The focus of research by UW ECE Assistant Professor Hossein Naghavi is very high frequency electronics in the terahertz range (100 gigahertz to 10 terahertz), which is a domain in between the microwave frequencies commonly used in cell phones and higher frequencies used in optical technologies. Naghavi directs the Terahertz Integrated MicroElectronics lab at the UW, where he designs analog microchips for imaging and spectroscopy applications and high-speed communications. Because terahertz frequencies have the potential to enable the user to see through optically opaque materials, Naghavi’s research has applications in biomedical sensing and imaging as well as surveillance and security. Also, the unique ability of terahertz frequencies to resonate with macromolecules, such as proteins and DNA, could create new opportunities for cancer cell detection and pharmaceutical research.

Naghavi is working toward improving microchip performance by exploring new ideas, theories, and techniques derived from physics and implementing them in existing microchips using traditional fabrication methods. By doing so, he aims to leapfrog over existing chip technology and significantly improve chip performance. His industry collaborators include GlobalFoundries and STMicroelectronics. These companies help to support research opportunities in his lab for graduate and undergraduate students. Naghavi is also aiming to incorporate advanced electromagnetic courses into UW ECE curriculum, which will provide important knowledge for students who want to design high-frequency terahertz chips.

He noted the importance of the CHIPS and Science Act to workforce development and how UW ECE is playing a crucial role in this endeavor.

“We need to train more and more engineers to become familiar with this chip design process because of the CHIPS Act,” Naghavi said. “Traditionally, most Ph.D. students in the circuit design area are able to fabricate these chips after two or three years of study. But now, undergrads will also have this opportunity. In the coming years, we will have more students in this circuit domain because of these opportunities that are coming.”

Chris Rudell

UW ECE Professor Chris Rudell

UW ECE Professor Chris Rudell develops analog chips that can be implemented in low-cost digital silicon technologies. His work integrates both digital and analog components on the same chip. He directs the Future Analog Systems Technologies lab at the UW, which explores a broad range of topics related to analog, mixed-signal, radio frequency, and millimeter-wave circuits. His lab focuses on developing novel architectures and circuits that can overcome current performance challenges and limitations with respect to speed, power consumption, signal fidelity, and costs associated with advanced silicon complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor, or CMOS, technologies. Rudell’s work has applications in high-speed wireless communications (1 to 100 gigahertz), neural engineering, biomedical interfaces, and quantum computing. He has become well known for his work in full-duplex communication, designing chips that can send and receive large amounts of data at high speeds while minimizing signal distortion and conserving bandwidth available for wireless communication. He recently gave a keynote talk on this topic at the 2024 European Microwave Conference.

Rudell is an experienced chip designer, and he has many industry sponsors and collaborators that support his research, such as Qualcomm, Boeing, Google, Medtronic, and Intel. His lab includes graduate and undergraduate students, and he is actively involved in shaping undergraduate education at UW ECE. He recently helped to develop an integrated system curriculum pathway for students interested in learning about chip design and development. He also put together a course for students to learn how to do a chip tape-out (the final stage for microchips before they are sent to manufacturing), which was a first for the UW.

“What we do in my lab is build chips,” Rudell said. “I’m always looking for bright students that want to contribute and try out new ideas, whether that be a novel circuit or system concept, or perhaps exploring compatible AI concepts which assist our analog hardware. My lab provides enormous opportunities for students, and we’re only limited by the amount of funding I can generate.”

UPWARDS for the Future Network

UW ECE and Physics Professor Mo Li

UW ECE and Physics Professor Mo Li is the Department’s associate chair for research and a principal investigator in the U.S.-Japan University Partnership for Workforce Advancement and Research & Development in Semiconductors (UPWARDS) for the Future Network. UPWARDS brings together six American universities and five Japanese universities with Micron Technology to provide advanced training and research opportunities that will grow the semiconductor workforce and help the United States and Japan build more of the microchips that both nations need. A total of $30 million in funding is available for this collaboration, including a $10 million grant provided by the National Science Foundation’s new Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships, which was authorized by the CHIPS Act. Matching funds were provided by Micron and Tokyo Electron. Li is a principal investigator for the grant alongside David Bergsman, who is a UW assistant professor in chemical engineering.

“The UPWARDS for the Future program sets a prime model of government-industry-academia partnership, propelling the development of the U.S. semiconductor technology workforce,” Li said in a UW News press release. “This initiative stands out with an emphasis on international collaboration, providing students with invaluable insights and experience into the industry’s international supply chain dynamics.”

Li directs the Laboratory of Photonic Systems at the UW, where he and his research team study integrated photonic systems, optoelectronic materials, and quantum phenomena. He develops novel devices and new technologies for communication and computation, optical sensing, imaging, infrared detection, chemical and biomedical sensing, and neuroscience. Li has worked with CoMotion at the UW to develop and license technologies he has created, and he has received support from their Innovation Gap Fund. He is also a faculty member of the Institute for Nano-Engineered Systems at the UW and QuantumX, which pioneers the development of quantum-enabled technologies at the University.