Article by Wayne Gillam, photos by Ryan Hoover / UW ECE News

UW ECE Assistant Professor Kim Ingraham designs personalized, adaptive control strategies for assistive robotic devices, such as exoskeletons and powered wheelchairs. Her work involves bringing students and faculty from different backgrounds and disciplines together to move toward a common goal of producing more usable assistive robotic devices for people with disabilities.

Millions of people have seen the Iron Man movies, in which the main character is empowered by a robotic exoskeleton. And millions more have watched the scene in Star Wars where Luke Skywalker receives a mechanical, touch-sensitive prosthetic hand that is wired into his nervous system. Because exoskeletons and smart prosthetics actually exist today, many might assume that we are only a few steps away from bringing this advanced technology we see on the movie screen into people’s everyday lives.

But the reality is that implementation of smart prosthetic systems and wearable robotics, such as exoskeletons, is not that simple. Robotic and mechanical systems can do some amazing things on their own, as this Boston Dynamics video demonstrates. But once a human being is brought into the equation, with all the complexities the human brain and body entail, it is a different story. What might appear on the surface to be a straightforward matter of creating a human-robot interface is, in reality, a difficult and complex engineering problem.

UW ECE Assistant Professor Kim Ingraham is addressing this multifaceted challenge in her lab, where she designs personalized, adaptive control strategies for exoskeletons and powered wheelchairs for young children. Her work is primarily aimed at creating usable assistive robotic devices for people with disabilities, and it is highly interdisciplinary, drawing tools and knowledge from robotics and controls, neural engineering, biomechanics, and machine learning.

“UW ECE is such a strong department in my research area. It’s a national leader in neural engineering as well as robotics and controls. And my work sits at the intersection of those two areas.” — UW ECE Assistant professor Kim Ingraham

Ingraham is also co-author of a new paper in the journal Nature, which examines ways to optimize and customize robotic assistive technologies built with humans in the device control and feedback loop. The paper brings together researchers from around the world who are working on human-in-the-loop optimization for assistive robotics. It explores over a decade of scientific research in the field, defines some of the key challenges, and highlights some of the current work being done in this area. Ingraham’s contribution to the paper draws from her doctoral research estimating energy cost using wearable sensors and including human preference as an evaluation metric for assistive robots.

“The fundamental challenge in the field is that historically we have studied the way humans naturally move and then we have built robots that can mimic that movement. But when the human is wearing the robot and they’re both in the control loop at the same time, we have to figure out ways for those systems to successfully interact,” Ingraham said. “Understanding and designing for the complexity of the interactions between the robot and the human is one of the big gaps that we still have to address.”

To help close these sorts of knowledge gaps, Ingraham oversees several different research projects that study and develop personalized, adaptive control strategies for assistive robotic devices. Although she is focused on designing assistive technologies for rehabilitation or for people with disabilities, she also works with augmentative devices, such as exoskeletons for nondisabled people, to better understand how robotic assistance impacts human motion. The engineering knowledge she gains from this research helps to inform her work and enables her team to design better device controllers.

An interdisciplinary path leads to UW ECE

Ingraham helps UW ECE doctoral student Zijie Jin put on a Biomotum SPARK ankle exoskeleton for an experiment in the UW Amplifying Movement & Performance Lab. This experiment is designed to help better understand how robotic assistance from an exoskeleton affects how participants walk, how much energy they consume, and how they feel while using the device.

As an undergraduate student in her freshman year at Vanderbilt University, Ingraham participated in an Alternative Spring Break program, which took place at Crotched Mountain Rehabilitation Center, a rehabilitation facility for people with disabilities. There, she was exposed to technology that supported people’s mobility and other activities in their lives, such as a powered wheelchair with an attached, adaptive knitting setup that allowed the user to knit using only one hand. The experience inspired Ingraham, and she became excited about the idea of using engineering skills to build assistive technologies.

In 2012, after receiving her bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering, she went on to apply to graduate schools. Unfortunately, she wasn’t admitted on her first attempt. She said this was not because she didn’t have good grades or research experience, but because she lacked an understanding of what she calls the “hidden curriculum” required for graduate school admission. According to Ingraham, this hidden curriculum includes acquiring a deeper understanding of the graduate admissions process as well as finding effective ways to demonstrate solid academic ability and research experience.

She moved on to secure a position as a research engineer at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (formerly the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago), where she worked from 2012 to 2015. It was there, in a hospital research setting, that Ingraham gained the knowledge and skills she needed to make it into graduate school.

“I learned everything at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. I had an absolutely phenomenal mentor, Annie Simon, and the director of our group was Levi Hargrove, and they were both incredibly supportive,” Ingraham said. “In particular, Annie taught me how to be a good researcher. She taught me things like how to conduct a good experiment, how to write a good paper, and how to be a really compassionate mentor while still maintaining high expectations.”

After three years at the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, Ingraham applied to graduate school again. This time, she was admitted to the University of Michigan, where she went on to earn her master’s and doctoral degrees in mechanical engineering in 2021.

Ingraham’s interdisciplinary background ended up leading her to the UW and to UW ECE. From 2021 to 2023, she was a postdoctoral fellow at the UW Center for Research and Education on Accessible Technology and Experiences, known as CREATE, with advisers in mechanical engineering and rehabilitation medicine. Toward the end of her fellowship, a colleague encouraged her to apply for an open faculty position at UW ECE because it appeared to be a good fit for her background.

“I originally thought, ‘I’m not in ECE, that doesn’t make any sense.’ But then, I started looking more in depth at the faculty and really saw how UW ECE is such a strong department in my research area,” Ingraham said. “It’s a national leader in neural engineering as well as robotics and controls. And my work sits at the intersection of those two areas.”

With that in mind, Ingraham applied, and in January 2023, she became a tenure-track assistant professor in the Department.

Research projects and collaborations

A closeup of the Biomotum SPARK ankle exoskeleton. This device is adjustable and can be worn by children or adults.

Ingraham’s research at UW ECE involves bringing students and faculty from different backgrounds and disciplines together to move toward a common goal of producing more usable assistive robotic devices. The ECE doctoral students in her lab have degrees from a wide range of disciplines, including chemical engineering, biomedical engineering, neuroscience, and anthropology. Ingraham said she believes this diversity of backgrounds highlights the Department’s general philosophy of expanding the definition of who can be an ECE doctoral student. She also said that these students bring multiple perspectives that contribute to her research, and they are thriving in the UW ECE doctoral program.

Ingraham collaborates with faculty in UW ECE and from different departments across the University on a wide range of research projects. She is also a core faculty member in the Amplifying Movement & Performance Lab, an interdisciplinary, experimental lab shared by faculty from the UW College of Engineering and the UW Department of Rehabilitation Medicine. One aim of her research in the AMP Lab is to design adaptive algorithms for exoskeletons. To this end, she is collaborating with UW ECE Associate Professor Sam Burden to develop game theory algorithms to customize robotic assistance from an ankle exoskeleton. In another project at the AMP Lab, she is collaborating with UW ECE Professor Chet Moritz, who holds joint appointments in rehabilitation medicine, physiology, and biophysics, and is co-director of the Center for Neurotechnology. Ingraham and Moritz are working to combine transcutaneous (on the surface of the skin) spinal stimulation with exoskeleton assistance. This is groundbreaking work primarily for adults with spinal cord injury. She is also building on her postdoctoral work at CREATE by studying how early access to powered mobility devices impacts development, language, and movement in young children. It is research that involves the “Explorer Mini,” a small, colorful, joystick-controlled, powered mobility device for toddlers. In this work, Ingraham is collaborating with her previous postdoctoral advisers, professors Kat Steele in mechanical engineering and Heather Feldner in rehabilitation medicine.

Ingraham noted that she appreciates the interdisciplinary opportunities UW ECE provides.

“Something I really value about being in our Department is how interdisciplinary it is, how someone with a nontraditional background like myself can still have an intellectual home in the ECE department, just because of how many areas ECE touches,” Ingraham said. “It was the people and research strengths that got me excited about UW ECE. I wouldn’t necessarily belong in every ECE department, but UW ECE is a really awesome fit for me.”

Work as an educator

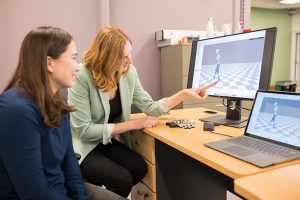

Ingraham examines experimental biomechanics data with UW ECE doctoral student Annika Pfister as displayed by an open-source musculoskeletal modeling and simulation platform called “OpenSim.” This data was collected from a participant with a spinal cord injury who was walking. Ingraham is pointing out to Pfister the angle of the participant’s ankle onscreen

Ingraham teaches undergraduate and graduate courses at UW ECE. She also leads a capstone course that includes both undergraduate and graduate students, the Neural Engineering Tech Studio. This is a cross-disciplinary course in UW ECE and the bioengineering department, facilitated by the Center for Neurotechnology. In the course, students design engineering prototypes based on neural engineering principles. The experience is structured to help teach students entrepreneurship skills as well as a user-centric thought process.

“I like teaching very applied courses,” Ingraham said. “I like it when students can see how what we’re doing in the classroom actually matters for real-world applications, how it manifests in research, industry, and technology we use every day.”

In addition to her duties as a researcher and an instructor, Ingraham is also chair of the UW ECE Colloquium committee. The Department’s Research Colloquium Lecture Series features research talks given by experts in electrical and computer engineering. Ingraham said that she and the committee are working hard not only to bring people in from across the nation to give these talks but also to build community in the Department through the lecture events.

For students interested in pursuing a career in robotics, Ingraham recommended learning the mathematical foundations of the field as early as possible. After gaining a firm grasp of the fundamentals, she said it was then important to find a niche within an application area to focus on. For Ingraham, that niche is assistive robotic technologies, and she noted how her professional goals and personal interests converge in this area.

“From a scientific perspective, I’m really interested in understanding how humans and wearable robots co-adapt to each other,” Ingraham said. “From a human point of view, I would really like to achieve the translation of our research into robotic systems that help people in meaningful ways — systems that can be adapted, personalized, and give people more choices in how they move around the world.”

For more information about UW ECE Assistant Professor Kim Ingraham, read her recent paper in Nature, and visit her faculty bio page or lab website.